Hey, American people of Mexican descent! What do you call yourselves? You know what I mean. When people ask: “so, what are you?”. A person—I think.

Personally, I like to call myself a Brownie but when I am amongst polite society, Hispanic or Mexican-American have usually been go-to’s. Though when I think about it, Hispanic is kind of vague and I was born in America, therefore I am an American first. Why do I have to specify? I’m a god damn Yankee doodle dandy and don’t you forget it.

I could just say American of Mexican descent but I run out of breath every time I try. I’ve never referred to myself as a Latina but if other people call me that, whatever. I guess I technically fit in that category. Just don’t call me a spicy Latina. I’m the type of Latina that quietly stews until I snap one day and reach unadulterated Bill Burr-levels of blind rage.

But I’ve been hearing the term Chicano more and more lately. And I don’t hate it. Chicano is efficient and accurately describes “what I am”: an American of Mexican descent. Once a derogatory term for us Brownies, those in El Movimiento or the Chicano movement adopted the label and made it their own in late 1960s America. And that’s how it’s done. Take the power out of hateful words and reclaim them for yourself.

And right now, the story of Chicano-ness is being celebrated in two major art institutions across Dallas and Fort Worth simultaneously—and it’s not even Hispanic Heritage Month! From lowriders at the Dallas Museum of Art to political printmaking at the Amon Carter Museum, the cultural history of Mexican descendants in post-war America is center stage in North Texas.

Guadalupe Rosales: Drifting on a Memory at the Dallas Museum of Art

Cruising into the Dallas Museum of Art, you’ll immediately be sucked in by the bold colors of red, orange, pink, and yellow stretching down the Concourse as you enter the memory of an artist. Stop and see your own reflection in the large rearview mirror hanging above the corridor to become part of the memory yourself. Surrounded by a glittering disco ball above, vague sounds of música, and glowing lightboxes with old photos of friends and Homies figurines took me back to a time I never really knew with Guadalupe Rosales: Drifting on a Memory.

I was a kid back then but can you imagine how bumping the lowrider scene must have been in East LA during the 90s? Oh my god—the music only. Well, Los Angeles-based artist Guadalupe Rosales takes you back to that nostalgic time with help from local artists Lokey Calderon and Sarah Ayala to deliver an immersive experience and homage to lowrider culture. Naturally, this got me thinking about the history of lowriders and what they mean for the Chicano community.

Lowriding after the war

Lowriding goes back to the 1940s, extending across Mexican-American barrios from East Los Angeles to El Paso, Texas.

Cue Sleepwalk by Santo & Johnny.

It all started with young zoot-suiters self-customizing their flashy Pachuco-style cruisers, but lowriders really took off after World War II. In general, car culture boomed in America once veterans returned home with all that GI money burning holes in their pockets. And Chicano servicemen were no different—they just did it their own way.

While high-speed hot rods were all the rage at the time, lowriders celebrated that “low and slow” life among the community. Often using cheap prewar Chevrolets or Fords, Mexican-American veterans customized their own cars by lowering the rear end within inches of the pavement and usually tweaked the engines, added soft velvet upholstery to the interior, or painted the exterior with metallic candy colors and stunningly elaborate designs.

Lowriders essentially became an expression of cultural pride and identity. These fly rides were (and still are) an extension of their owners and it was all about representing your individual style while cruising down the local boulevard. But honestly, it was about socializing with your community as much as it was about showing off your extravagant rolling work of art.

American car clubs have been around since the turn of the twentieth century, but by the late 1950s, customized cars began dominating the scene. In 1962, the Ruelas brothers (Julio, Fernando, Oscar, and Ernesto) opened their own club in Los Angeles called Duke’s Car Club which eventually grew into multiple chapters across the nation. It’s regarded as the oldest lowrider club that’s still in existence today, including one chapter in Japan!

By this time, the civil rights movement was already in full swing and by the end of the decade, young Mexican-Americans were also getting fed up with trying to blend into a society that treated them like second-class citizens. Chicano activists advocated for social/political empowerment and celebrated their Indigenous roots as opposed to just focusing on their Spanish or European side.

Meanwhile, lowrider car clubs also embraced the movement and even provided community services, like fundraising for the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union. The Chicano community banded together and this was reflected in the lowrider lifestyle to the rise of political printmaking amongst Chicano artists/activists in the 1960s.

¡Printing the Revolution! at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Mexican descendants are no strangers to the graphic arts. In fact, the first printing press in the Western Hemisphere was actually established in present-day Mexico City back in 1539! The printmaking tradition began with mostly religious imagery for churches, but fast forward to the nineteenth century, and printmaking—along with political discourse—further expanded among the masses with the introduction of lithography in Mexico.

I was actually lucky enough to work with rare prints by the father of Mexican printmaking José Guadalupe Posada and the following generation of Mexican printmakers José Clemente Orozco and Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) as an art librarian at my last library gig. Hence, the reason why I was so excited to hear about ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

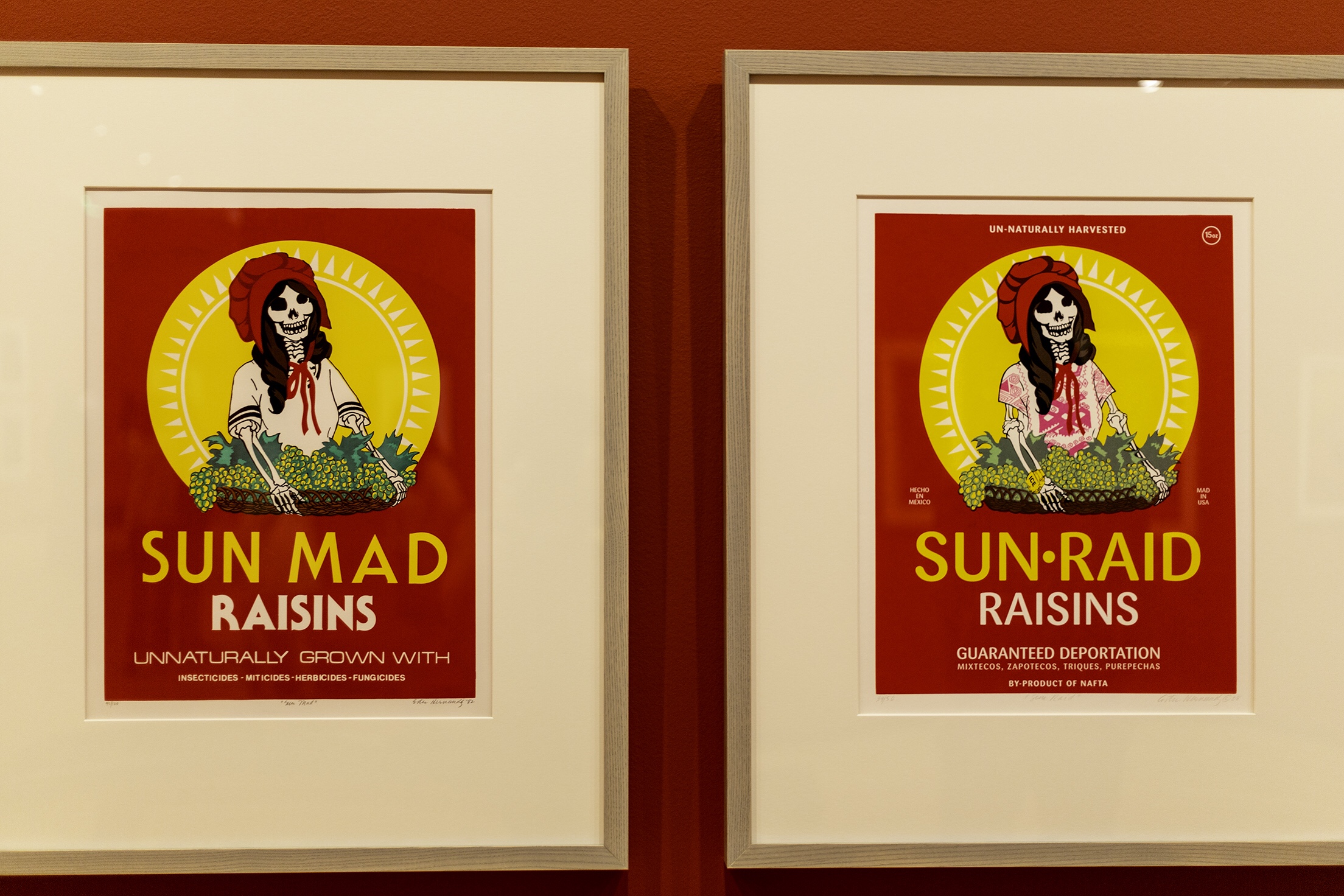

I eagerly walked upstairs toward the audacious red walls of the exhibition with a distinctive Emiliano Zapata detail gazing off to the side as I strolled through to see what happens when art and activism collide. Organized by Smithsonian American Art Museum curators E. Carmen Ramos and Claudia E. Zapata, ¡Printing the Revolution! features 119 prints by iconic Chicano artists, from Andrew Zermeño’s Huelga! (1966) to Ester Hernandez’s Sun Mad (1982) that demonstrate printmakings massive role in the Chicano movement.

In the 1960s, El Movimiento, also known as the Chicano movement, developed in the wake of the American civil rights movement to also demand equality in the eyes of the law and society while unifying Mexican descendants—regardless of class.

But grievances with the United States government go back to after the Mexican-American War ended. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848, and the border soon crossed the Mexicans already living in what would soon become the American Southwest—from New Mexico to California. Land grants were initially promised to the Mexican people of this region but were ultimately denied when it came down to it.

So, you know how the story goes. Basically, Mexican descendants quickly began their status as second-class citizens the second the border crossed them. It took over a century for a new generation of Mexican-Americans to stand up, proudly adopt the “Chicano” label, and reject assimilation into Anglo-American culture. We have our own badass culture!

Come on—Mexican food, Mexican art, calaveras, Día de los Muertos, family, tequila, AND our ancestors come from the Aztec and Mayan Empires. We got our own stuff, okay? But, I digress.

Anyway, Chicano activists opted to embrace their newfound identity while exploring their Indigenous roots. And most importantly, they mobilized like never before. Chicanos fought for the restoration of land grants, labor rights, and better educational opportunities. Key figures to come out of the Chicano movement were poet/activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and civil rights activist Reies Lopez Tijerina, along with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta—co-founders of the National Farmworkers Association which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Like their predecessors down south, Chicanos in America used art—specifically printmaking—to not only express cultural pride but also to call attention to the blatant discrimination they saw happening around them…

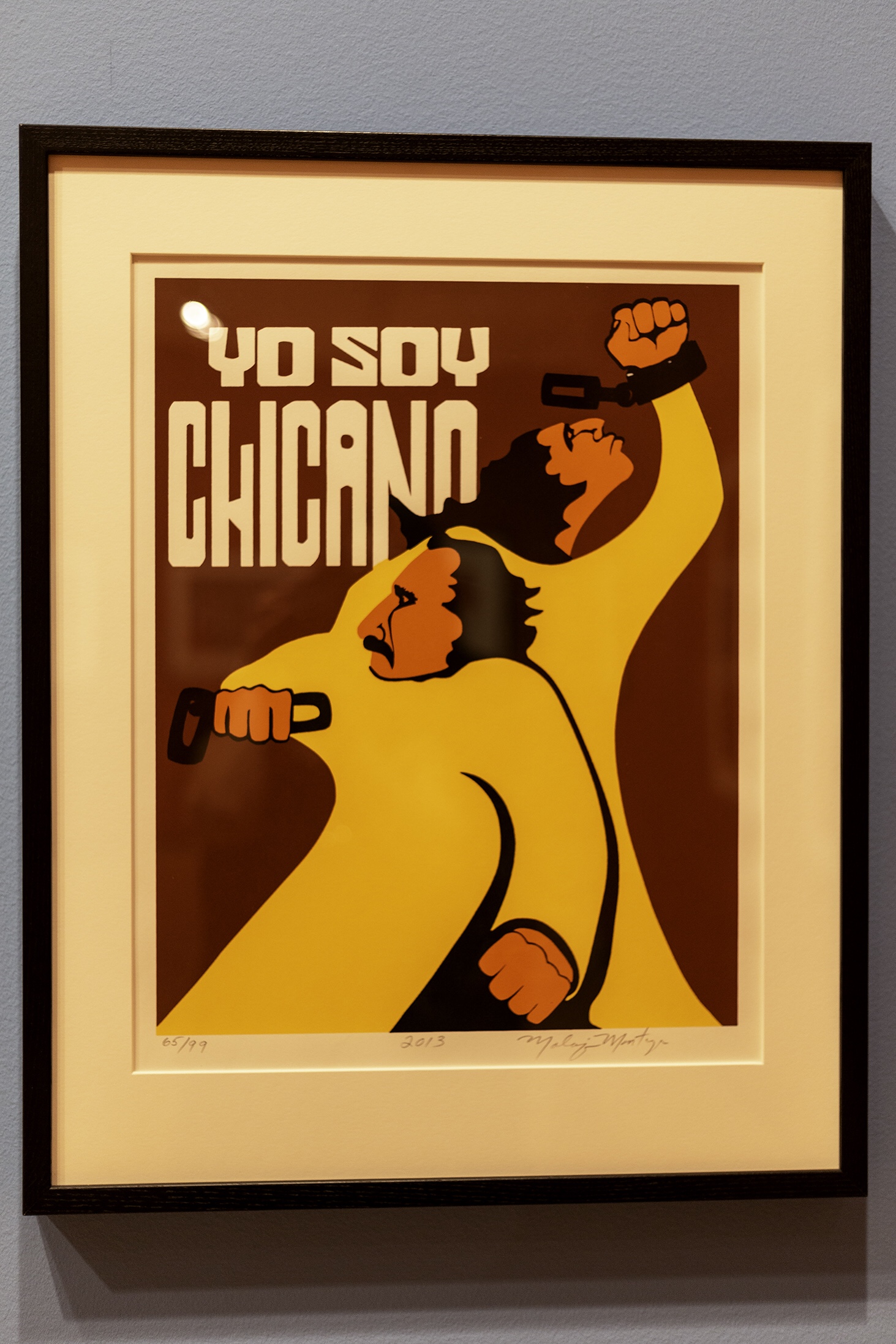

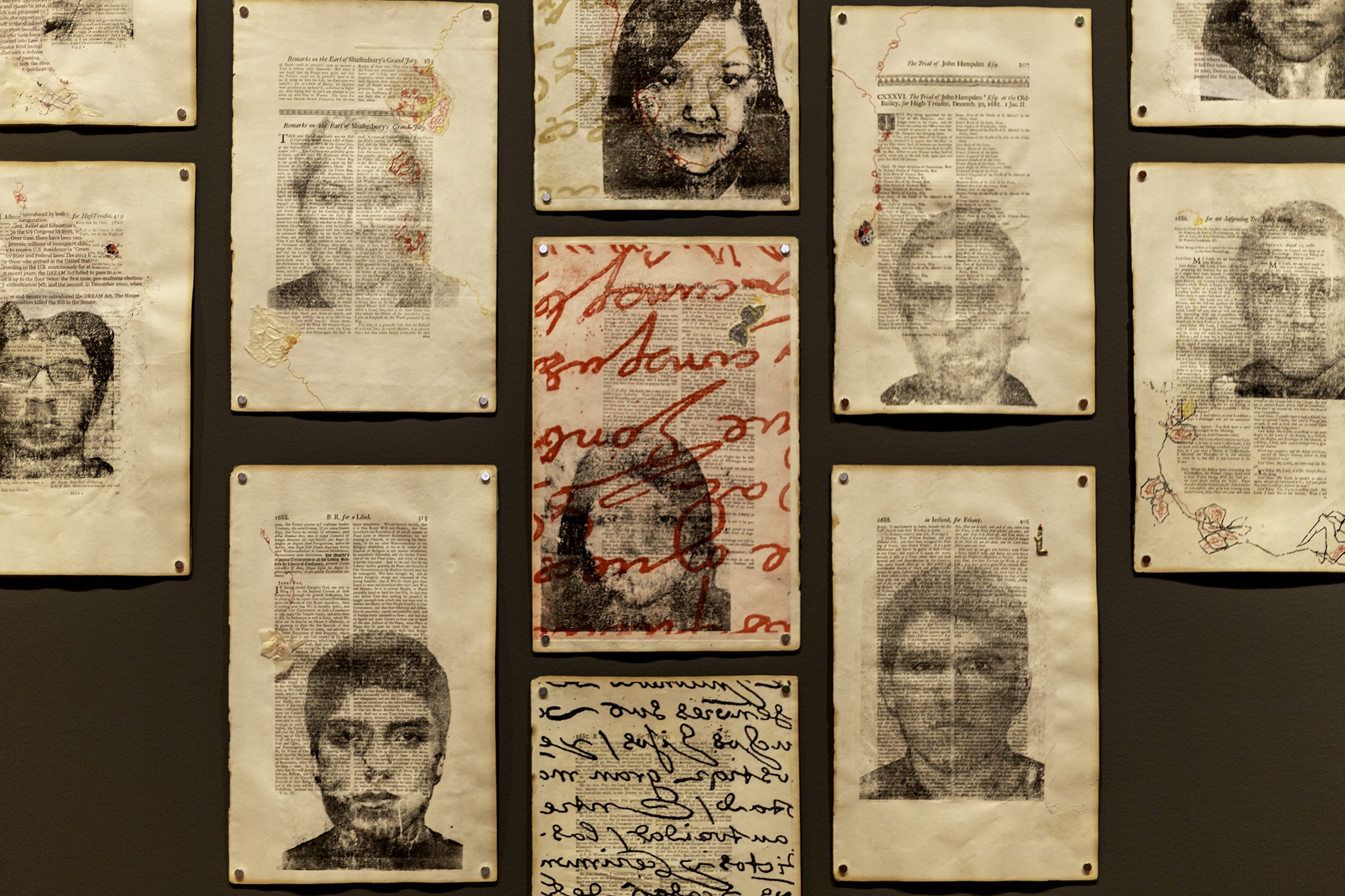

Some unapologetically declared who they were like Malaquias Montoya in Yo Soy Chicano (1972). Some called out the agribusiness for contaminated water and pesticides that affect farmworkers, consumers, and the environment as a whole like Ester Hernandez in Sun Mad (1982). Some reference how Dreamers and other undocumented immigrants are portrayed as criminials in some sectors of our society like Sandra C. Fernández in Mourning and Dreaming High: con mucha fé (2014-2018). And some just simply paid homage to other great Mexican and Mexican-American figures like José Guadalupe Posada, Emiliano Zapata, and Selena.

From lowriders in Dallas to political printmaking in Fort Worth, the fact that there are two major art institutions displaying a certain stretch of Mexican-American history after the war to now is pretty cool. And it’s had me reflecting on my own ancestry—on my own history. It makes me thankful for those who came before me. The ones who did the dirty work and demanded our civil rights in order to give me a relatively good life today. Nothing’s perfect, but that’s life.

Will I start calling myself a Chicano? Probably not. Mostly because I don’t like getting caught up in “labels” and I’m just not used to referring to myself that way. But also—I have a lot of fun calling myself a Brownie. We may not agree on what we call ourselves, and that’s okay. We are not a monolith. But we’re still united through our common hardships and triumphs as a people.

I think Rodolfo Gonzales said it best in his poem I Am Joaquín:

“La raza!

Méjicano!

Español!

Latino!

Chicano!

Or whatever I call myself

I look the same

I feel the same

I cry

And

Sing the same.

I am the masses of my people and

I refuse to be absorbed.”