Note: Here’s the first blog post in reference to a certain little proposal I previously proclaimed. This was my blog submission to join DPL’s blog team in 2019. For context, the prompt was: “Write about the 2nd most interesting thing on your floor (for Central branch) or branch. Don’t write about the most interesting thing. I want the 2nd most interesting thing.”

__________________________________________

From free music classes to rotating art exhibitions by local artists, there are many interesting things on the Fine Arts floor of the J. Erik Jonsson Central Library. Now, as Art Librarian, I find nothing more captivating than our superb art collections—it’s prints and artists’ books galore over here! But the second most interesting thing? That would have to be our Frank Lloyd Wright Music Stand.

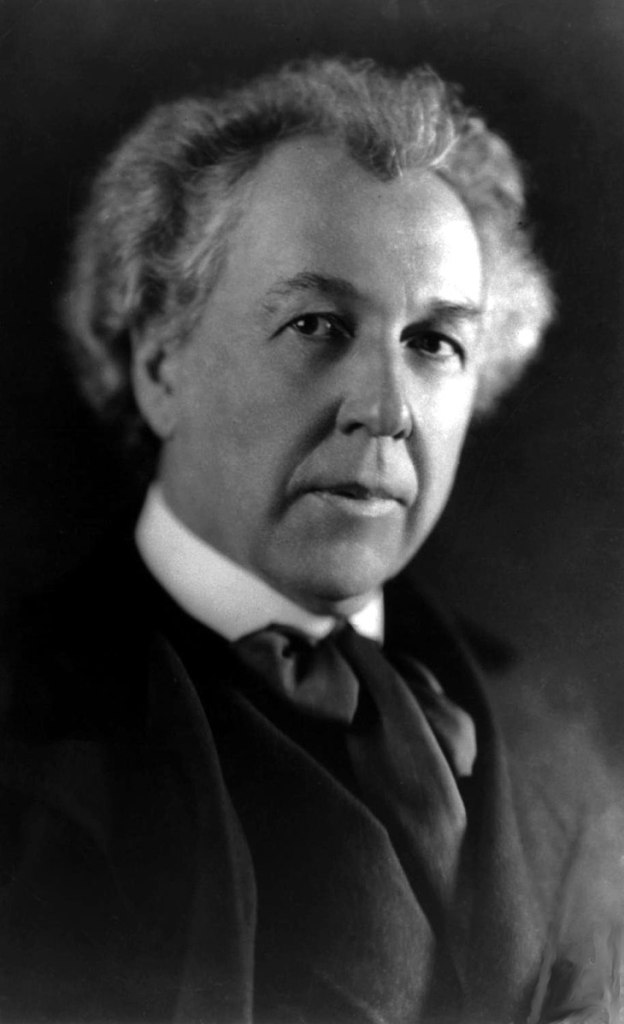

Arguably the greatest American architect of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright loved music as well, designing and building the visionary (yet impractical) music stand before us. Only six other music stands are known to exist in the world, and the Dallas Public Library was lucky enough to have accidentally acquired such a rare musical treasure.

“Accidentally?” you ask. Yes, accidentally.

Music played a profound role throughout Frank Lloyd Wright’s life and work, taking up the piano and violin as a child. It also didn’t hurt that his father, William C. Wright—a musician and preacher— taught him “to see a great symphony as an edifice, an edifice of sound, you see. So when I listen to Beethoven, who is the greatest architect who ever lived, I never fail to see buildings. He was building all the time. He was a great composer also. So never miss the idea that architecture and music belong together. They are practically one.”

In 1932, Wright and his wife, Olgivanna, created the Taliesin Fellowship: an apprenticeship program emphasizing the basic philosophy of “learning by doing” and community living. Under Wright’s guidance, aspiring architects lived, worked, and studied at his Taliesin estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin, in what could only be described as an all-encompassing learning environment.

Apprentices not only participated in carpentry, drafting, and furniture building— among other hands-on architectural tasks—Wright also encouraged his young protégés to explore different talents, such as cooking, sculpture, and music. Those who took up an instrument or sang were often invited to perform for the Wrights and their guests following lavish dinner parties frequently thrown at their home.

John Rosenfield, arts critic for The Dallas Morning News, and frequent visitor to Taliesin, wrote in his column, Frank Lloyd Wright Stand (May 6, 1956), that “very little that happens to Wright fails to stir the builder in him…the spidery wire music stands around which a string quartet deploys itself never has failed to irritate the host. Sooner or later Mr. Wright had to do something about it.”

And do something about it, he did. Wright soon designed a wooden one-piece quartet music stand, surmounted with an elegant canopy and four small lights installed underneath to illuminate the sheet music on each facade ledge. Rosenfield even commented that the amateur musicians playing on the sculptural stand “sound better because they look better.”

Rosenfield was so enamored by what he described as “a triumph of visual integration without distraction” that he persuaded the architect to build an exact copy of the music stand. It was delivered on April 1, 1956, and then displayed at The Dallas Morning News offices for a short period. Later, he placed the music stand on indefinite loan with the Dallas Chamber Music Society. The arts critic hoped the music stand would find a permanent home with the DCMS, as he imagined no musician would deny using an original Frank Lloyd Wright design to maximize their performance. However, Dorothea Kelly, artistic director of the DCMS, later confessed at a retirement dinner for Rosenfield that “the first concert we tried it, the musicians found it impossible to use. There wasn’t space to turn pages and the lights didn’t shine on the music.”

Did aesthetics mean nothing to these musicians?

Fortunately for us, the Dallas Chamber Music Society’s loss was the Dallas Public Library’s gain. As it happened, Rosenfield was close friends with George Henderson, manager of the Fine Arts Division at the J. Erik Jonsson Central Library, who wanted to borrow the music stand for an exhibition at the library. Sometime later, Kelly was confronted by DCMS President Howard Payne, who “asked why I had given away the stand without the knowledge of the board. ‘Given away?’ I asked in amazement. ‘Yes,’ said Mr. Payne, ‘haven’t you seen the lovely plaque on it which says, ‘Given to the Public Library by The Dallas Morning News and John Rosenfield?’” Perhaps Rosenfield gifted the music stand to DPL himself, as it was not as appreciated by the DCMS as he had hoped. As far as the rest of the Society was concerned, it was accidentally given to the Dallas Public Library.

You know what they say (and by “they” I mean the late, great Bob Ross): “We don’t make mistakes, we have happy accidents”.

Rosenfield and DPL were not the only ones who admired the imaginative music stand, as six others are known to exist today. Wright kept three for himself in his Taliesin (Wisconsin) and Taliesin West (Arizona) estates. A fourth stand resides at the Bethesda, Maryland home he designed for his youngest son, Robert Llewellyn Wright, while a fifth stand occupies the music room at the Zimmerman House at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire. The last music stand was built posthumously at the request of Wright’s widow as a gift for Lady Bird Johnson—now on display at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin, Texas.

As previously mentioned, there are many interesting things on the Fine Arts floor at the J. Erik Jonsson Central Library. But it is hard to compete with the simplistic, innovative design of the Frank Lloyd Wright Music Stand—no matter how impractical it is for “professional musicians”. Sometimes, you just have to suffer for fashion.